Heritage Breed Series ..take 1

I’m about a third of the way through the 195 breeds of the Livestock Conservancy’s Priority List. Right now, I’m into the sheep breeds. A friend asked me about my process, so I thought Id outline the process I go through in this project.

I started this series to jump start my painting practice. I wanted to create a big body of work, I wanted the paintings to be small, so I would be able to complete them in shorter painting sessions, and be a subject matter I would not have to be super precious with, but that held my interest. I am pretty much obsessed with heritage breeds, and I have been a member of the Livestock Conservancy for several years. I am raising as many heritage breeds as Ed will let me have on our farm. So, I figured that would be a great place to start. Little did I know how much more it would become.

I did not know how much other people would be interested in what I’m doing. Through the website and my Instagram and Facebook pages, I have received a lot of feed back and interest in the project. The paintings have also been selling. I didn’t realize how many other people have my same interest in these breeds. Through the project I have connected with and learned from so many farmers and producers, here in the US and all over the world.

Here is a sample of three of the sheep breeds I have been painting:

When I decide on a breed to paint, I start the search for reference materials. I read up on the breed, its history and where it is likely to be raised.

Gulf Coast Sheep are a very old breed developed from sheep that the Spanish first brought to the southeastern United States in the 1500’s. They mixed with the sheep imported by the French to Louisiana. Descendants of these sheep developed under humid semitropical range conditions in the Gulf Coast areas of East Texas, Louisiana, Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Florida.The sheep free ranged in unimproved pastures, piney woods and sugar cane fields. These sheep have been known by various names such as Florida Native, Louisiana Native, Common Sheep, Woods Sheep, Native Sheep or Pineywoods Sheep. After World War II, these breeds were replaced with sheep which were larger in size and produced more wool and meat. Remnants of these sheep survive today and are known as Gulf Coast Sheep. These sheep are extremely heat tolerant and are especially resistant to parasites, making them very attractive to regenerative farmers and small holdings in the south. Gulf Coast sheep lack wool on their faces, legs, and bellies, an adaptation to the heat and humidity of the South. Otherwise they tend to vary somewhat in aspects of physical appearance. While most sheep are white, blacks and browns also occur, and some individuals may have spotted faces and legs. Most rams and some ewes are horned, although both sexes may also be polled. Gulf Coast sheep vary in size, with rams weighing 125–200 pounds and ewes 90–160 pounds. Gulf Coast breed and lamb year-round. The ewes make excellent mothers, pasture lambing without assistance. With good forage, incidence of multiple births increases.

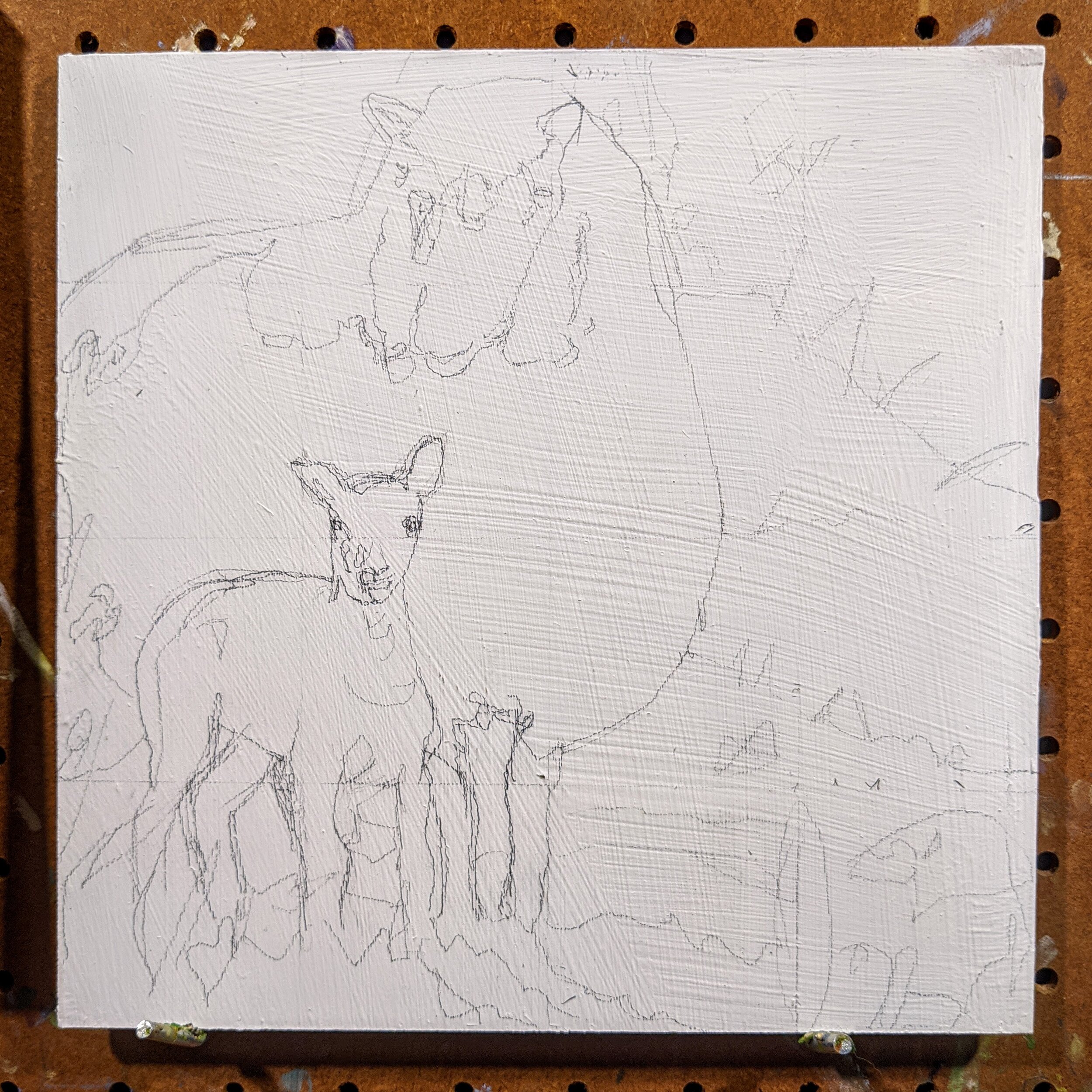

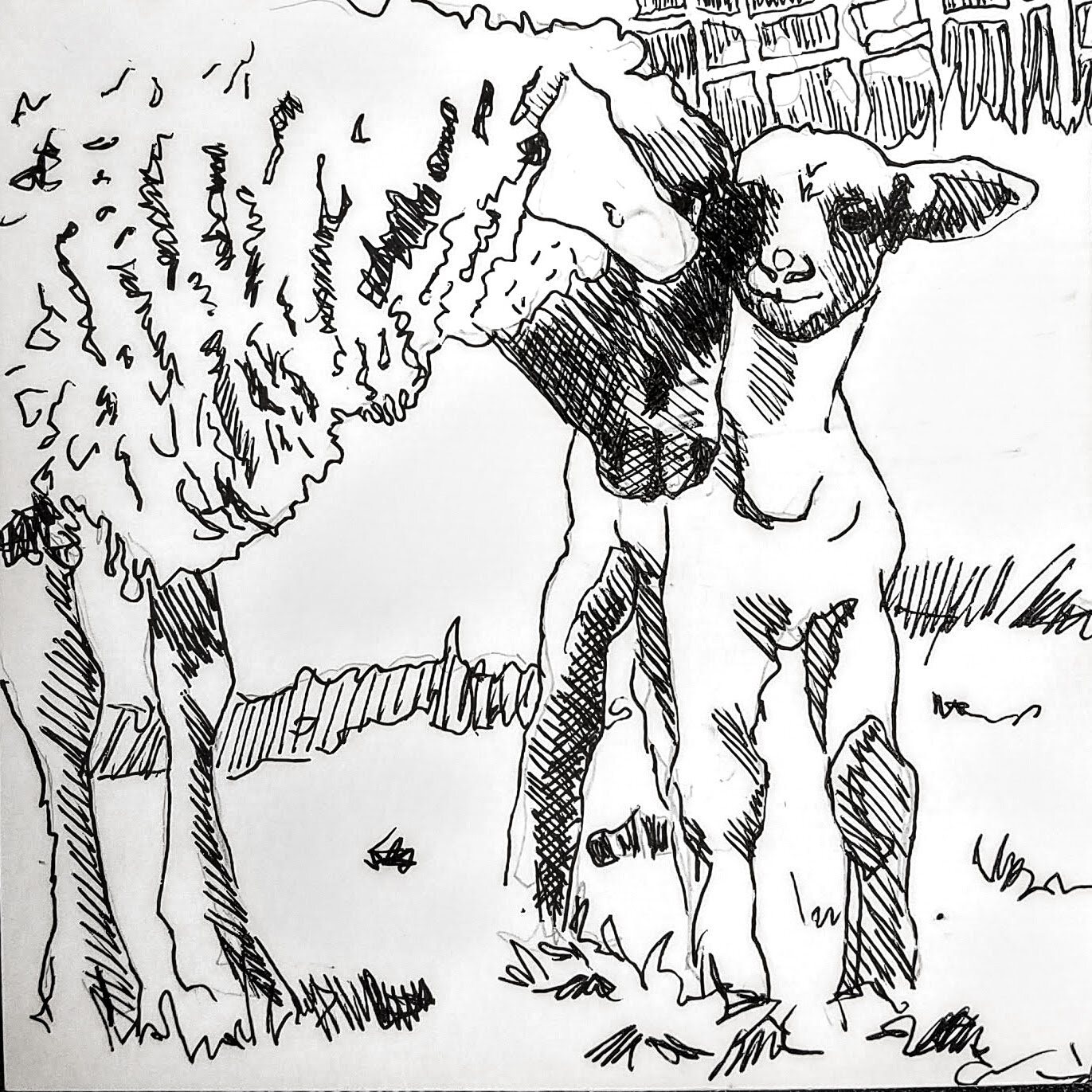

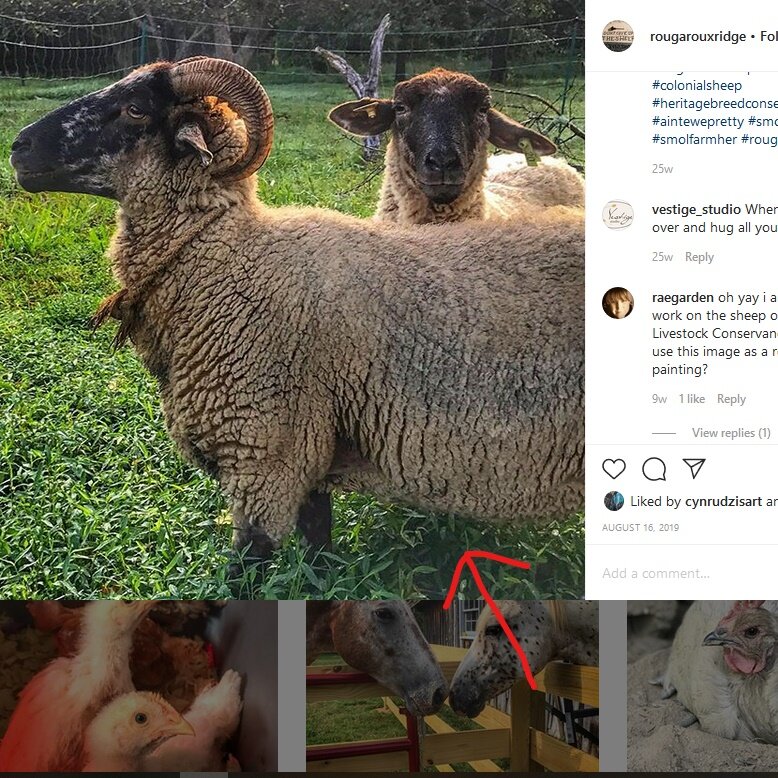

Next, I track down some good reference materials. The internet is a saving grace for this task. I am not sure how I would do this project without it. I google search images of the breed, check out breed associations, Facebook groups, and Instagram hashtags. I love this part. I just pour over the images, and any that speak to me, I tag and group in a folder in Dropbox. That’s so I can add them from my phone or PC or laptop. Once I have a good group. I go through them and try to link them to the original site. If I can find a contact, I ask permission to use the photo as a painting reference. I used to be a little nervous about this part, but I have been delighted that people give permission with enthusiasm for the project and appreciate the recognition. Once I have a composition worked out, I make a preliminary drawing on white gessoed panels that Ed cuts to size for me. After I have about 5 drawings I get going.

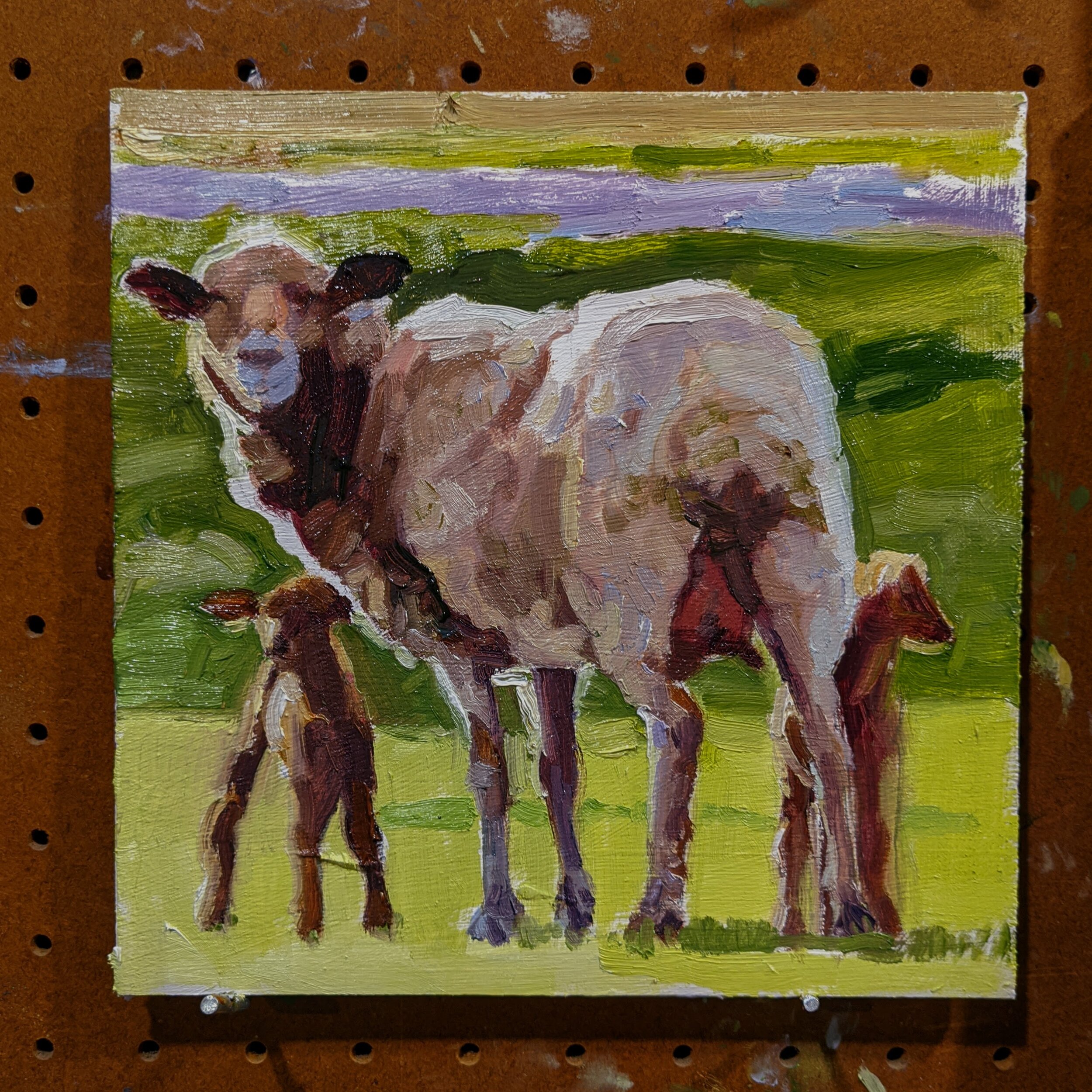

I usually work on about 5 at a time. I like to get the basic composition down with general values and color down. I like to work the whole painting, all over. Instead of working one area to finish, I work the whole painting from loose and general to more refined. That way it ‘bakes’ at the same rate. No crispy parts or raw parts. I want there to be a good likeness of the animal, but I don’t make photo-realistic images. I make paintings. I love the loose painterly strokes that oil paint makes. I want the paintings to be beautiful compositions of light and color, glimpses of an animal in its natural habitat, alone or with a companion. Each one is different, each a new challenge or problem I give myself to solve.

Florida Cracker Sheep are very similar in their history to Gulf Coast Sheep, only they are geographically tied to the Florida Peninsula. Originating from the sheep brought by Spanish colonists in the 1500’s they developed largely through natural selection under humid semitropical range conditions in Florida. They demonstrate great resistance to internal parasites. The ewes can breed back one month after lambing, and ewes can produce two lamb crops per year. These sheep can handle harsh climates and low-grade forage and still thrive.

I love this painting because it shows an ewe with twins and shows her in her typical habitat.

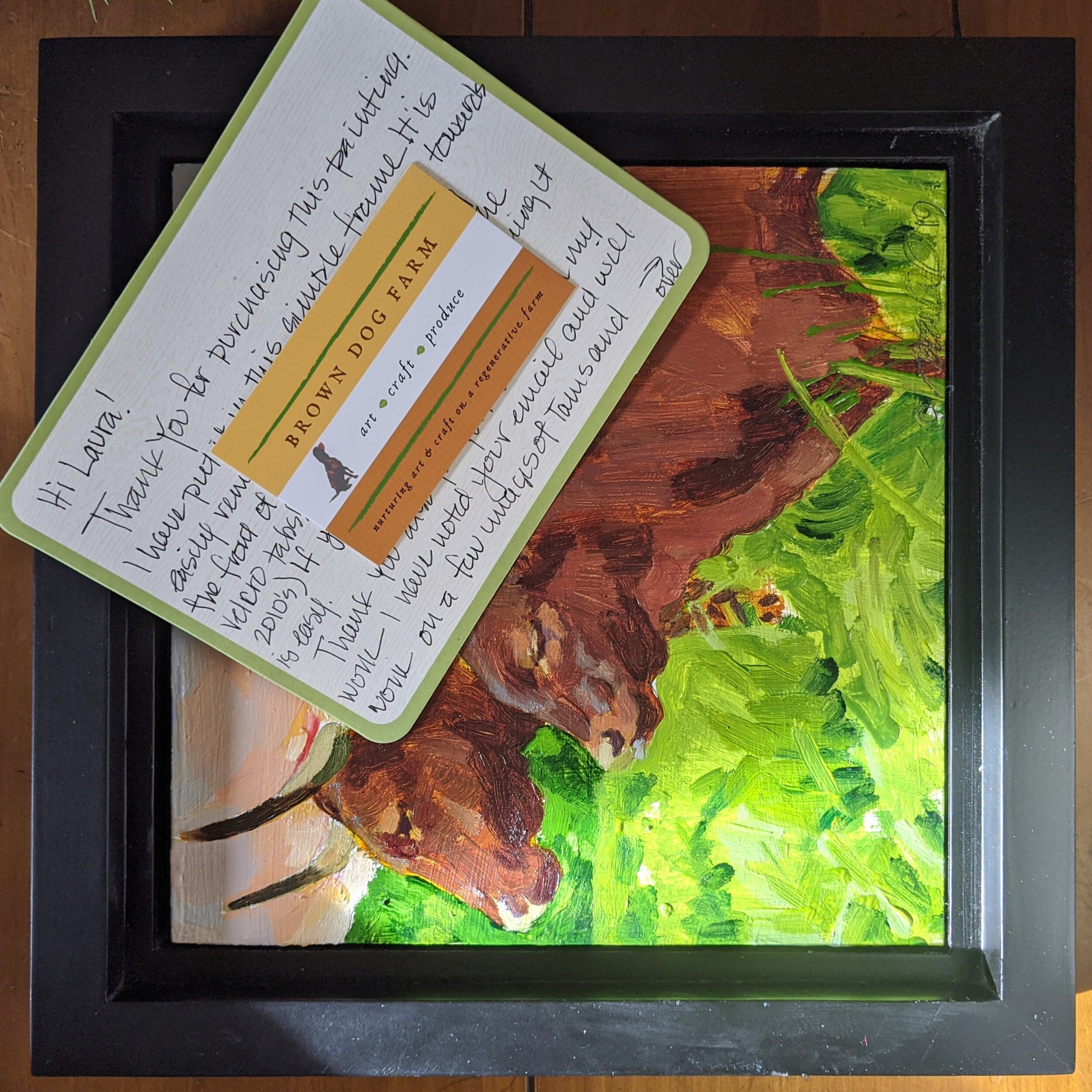

I usually finish the painting in 2 sometimes 3 sessions. I try not to overwork them. I have a lot of them to get done so I try to make them quickly and then move on. Once they are done, I leave them on the wall to dry. I post them on my social media sites, and almost immediately begin to get feedback. I always try to tag the producer, farm where they come from, or owner. It is even better if I know the name of the animals. Sometimes they sell! Once they are dry, I give them a final varnish. I have a frame supplier that makes a nice matte black floating frame they slip right into. I use Velcro strips on the back to attach the frame to the painting panel.

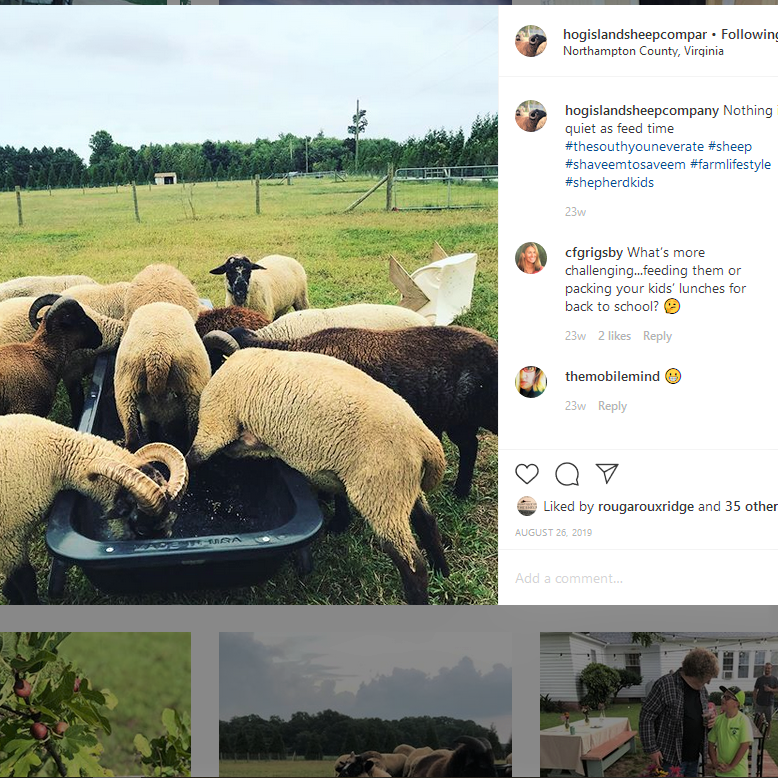

I found a beautiful image of a pair of Hog Island Sheep from Rougaroux Ridge Farm, in Virginia. The sheep are named Nettle and Thistle, and their owner Cynthia is painter and animal lover. We follow each other on Instagram and share our adventures of building our farms and sharing our experiences with others. This painting sold to another farmer who raises Hog Island Sheep in Maryland.

Hog Island Sheep have a fantastic story. Hog Island is a barrier island off the coast of Virginia. Early colonists brought sheep breeds from the British Isles. In isolation, the sheep herd developed in response to the islands habitat to be exceptional foragers, hardy and resilient. Isolation and natural selection developed a distinct breed. In the 1930’s a series of hurricanes and storms led the island residents to permanently relocate to the Eastern Shore of Virginia leaving the herd on its own. In 1974, The Nature Conservancy bought the island and over the next few years removed all the Hog Island Sheep to Virginia Tech for research into the breed’s parasite resistance. The year-long study indicated that isolation, not resistance, had kept the sheep virtually parasite free on the island. After their stay at the University many of the sheep were given to living history museums, including Plymouth Plantation, the Museum of American Frontier Culture, Mount Vernon Estate and Gardens, George Mason’s Gunston Hall, George Washington’s Birthplace, and the National Colonial Farm. Ewes may be horned or polled. Mature animals weigh between 90–150 pounds. The ewes make excellent mothers and most often give birth to twins. Hog Island sheep are excellent foragers, like goats many prefer to browse rather than graze. They stay in very tight flocks and are extremely alert in nature.

I never thought that this series would connect me with so many farming friends. We share images and stories of our farm journeys through images and posts, reading each other’s blogs, and subscribing to each other’s newsletters, and it makes me feel hopeful and not so alone in my farm goals. Most of all I am thrilled to share information and spread the word about the different breeds on the Livestock Conservancy’s List. I have pledged to donate 10% of all the sales of the paintings, prints, and calendars and note cards to The Livestock Conservancy to promote their good work in saving these endangered animals. I am thrilled at how far and wide these little paintings are traveling. I sent one off last week to Ireland. This year I get to write a big check!

Thank you to all of you who have purchased artwork , you have made this happen and I am so grateful.